This article was originally published on the website “Conscious Bridge“.

Ernest Holmes is the well-known spiritual teacher and founder of the New Thought philosophy, Science of Mind. Today, his teachings continue through his books, articles, audios and the classes at many spiritual centers, especially those who are a part of Centers for Spiritual Living.

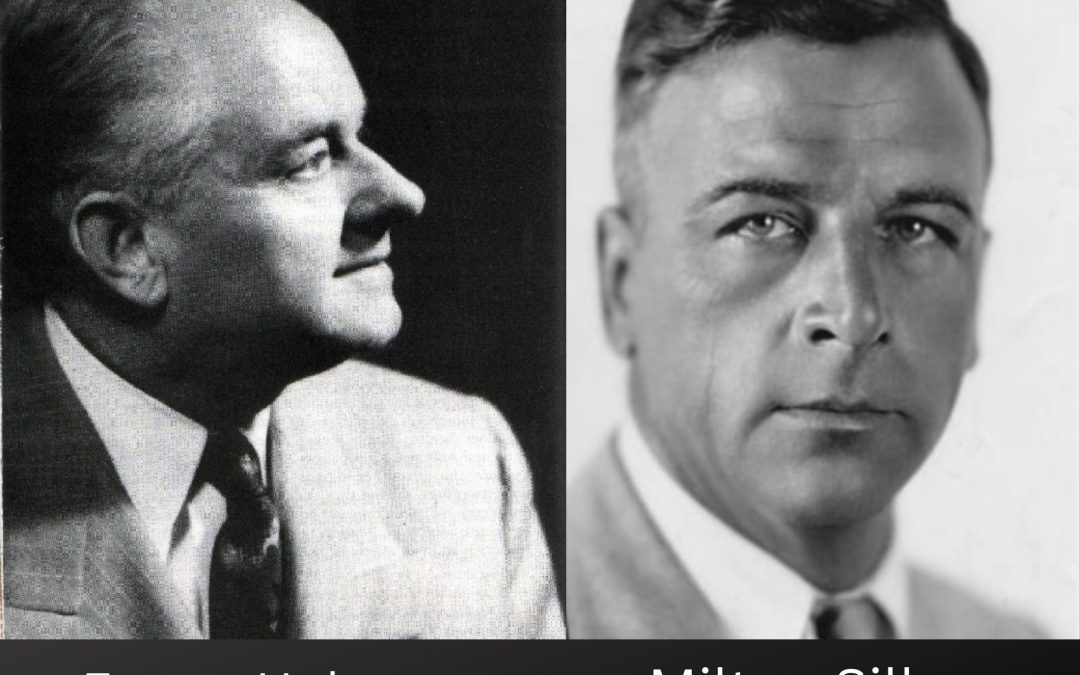

Although most of Holmes’ many books were written alone, there are a few that are co-authored with other individuals mostly with fairly well-known teachers in Science of Mind. However, one book is different – the small volume entitled “Values – A Philosophy of Human Needs” published in 1932 by the University of Chicago which was co-authored by an individual named Milton Sills.

Who was Milton Sills?

Most of us today may not be familiar with Sills, but he does rate a Wikipedia page. There you can read the details of his life as a stage and screen actor in the early part of the twentieth century. He has his own “star” on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame. Although he passed in 1930, you can find him on IMDB.

Of special note from his bios online is the fact that he was also a student of philosophy and served as a professor at the University of Chicago before his rise to fame as an actor. This fact played a role in the connection between Holmes and Sills.

According the Fenwicke Holmes’ biography of his brother, Ernest Holmes, His Life and Times, soon after establishing Science of Mind magazine, Willett L. Hardin, Ph.D., a scientist, became closely associated with Ernest” and “they decided to begin the publication of a new magazine under Dr. Hardin’s editorship, which would be called Quarterly Journal of Science, Religion and Philosophy.

Whereas Science of Mind would be the primary “publicly focused” periodical, Ernest felt that the “Journal” would allow for the sharing of more “scholarly” writings. For example, the Summer 1930 issue included a conversation discussion by “The Philosopher, The Scientist, The Psychologist, The Religionist and The Metaphysician” on the topic of “Is there a Conscious Intelligence in the Universe that responds to man?” Heady stuff indeed.

Fenwicke writes that Sills joined the staff of the Journal as an associate editor in the fall of 1930. Given that Sills’ untimely passing was in September 1930, this role was apparently short lived. The Journal itself was published for only a short while by the Institute of Religious Science before being turned over the University of Southern California who continued it for a few years more.

Although it’s not clear from Fenwicke’s writings when Holmes and Sills met, he does describe it occurring through connections made by Ernest’s wife Hazel stating “Hazel drew her own kind of people—people from the movies, artists, musicians. … and she was part of the work of such stars as Doris Kenyon and Milton Sills and many others.”

He goes on to describe how his brother “and Milton Sills who, with his beautiful actress-wife, Doris Kenyon, had become close friends of Ernest and Hazel, held long discussions on philosophy at about this time.” He added that “in 1932, after Dr. Sills’ death, these were published in a slim volume entitled Values which has since become a collector’s item.”

In his recollections, Fenwicke felt that “These dialogues were all reminiscent of Ernest’s and my early “library discussions” in the parsonage in Venice and our later questing exchanges with Dr. Ameen Fareed on psychiatry and with Rabbi Ernest R. Trattner on the cabala and represented a type of learning that my brother practiced throughout his life.”

In the Foreword to the book Values, Holmes wrote:

“This book consists for the most part of stenographic reports of actual conversations between Milton Sills and myself. The single exception is the dialogue on immortality, which has been written by me. It however in my opinion constitutes a fair representation of Milton Sills’s belief about the continuity of the human soul. It was our intention to cover this subject in our conversations. I believe that the dialogues will answer many questions about his philosophic outlook on life.”

Holmes described Sills as being “deeply spiritual, highly intellectual and bordered on the mystical”. He added that Sills believed in “emergent evolution” (as did Holmes) seeing it as an “ever ascending but never reaching a final goal” fostering an acceptance that eternity is not a place to attain but an “everlasting progress in which an individual never loses those elements essential to the continuation of a definitely individualized entity”.

Years ago, this small volume fell into the public domain and one can find reprints of it available for sale online. In the recent and ongoing efforts to inventory the works of Holmes [in my role as a board member and key researcher for the Science of Mind Archives] combined with the goal of making as much of this content available online via its website, it was recently discovered that this book had not yet been posted there. That oversight has been corrected, and the Archives is pleased to present this book for your spiritual development and enjoyment.

In these compiled transcripts, you can read the conversations between Holmes and Sills on the topics of Reality, The Creator in Creation, Values, Personality, Faith and Immortality. Fans of Holmes who are not familiar with this book will find it to be a great treat!

You can find it available on the Science of Mind Archives website here.

Mark Gilbert

————————————————————————–

To give you a “taste” of this book and their conversations, here is a brief excerpt from the chapter on “Faith”.

Mr. Sills: Has there ever been a time in your life, Ernest, when faith completely collapsed in you?

Mr. Holmes: Yes, there have been times when my faith was temporarily lost, when I could not seem to hold on but it has always returned and with greater conviction.

Mr. Sills: There have been times in my life when my faith so completely collapsed that I did not believe in anything, when a sort of universal skepticism crept over me. However, even at that time some vestige of faith must have remained or I could not have lived from moment to moment.

Mr. Holmes: Don’t you think, Milton, that all men really live by faith?

Mr. Sills: I do and I mean by that that they live by assuming certain things to be true that they cannot prove by reason or intellect.

Mr. Holmes: Don’t you think that the lives and experiences of people have proved that their faith has been justified?

Mr. Sills: Yes, I do, but not intellectually, pragmatically rather. I believe that the whole ascending edifice in which we live and move and have our being is sustained by faith and not by intellectual reasoning.

Mr. Holmes: It seems to me, Milton, that there is something in us more fundamental than the intellect. One thing is certain, that in so far as a man loses faith in life and in people he is lost, intellectually and spiritually. He becomes, temporarily at least, a hopeless sort of individual.

Mr. Sills: That is true.

Mr. Holmes: It is also true that as one regains a natural and spontaneous faith in life, he is given back to himself, he becomes happy and useful to the world.

Mr. Sills: I think such a person can be called “twice born.”

Mr. Holmes: Yes. There is such a thing as being twice born. I suppose we are all changing, being reborn into a greater experience every day.

Mr. Sills: I should like to become a little more concrete at this moment and say that most of the things that we believe, we believe on hearsay; we take them for granted. I, for example, must believe on hearsay what my mother and father told me, that they were my parents. I must believe on hearsay that my brother was born of the same parents. I have no memories of my own birth, nor of my brother’s birth. I have no knowledge of an eye-witness sort, of events connected with my birth or my brother’s birth. It is possible to question whether a world external to myself exists but interaction with that world forces me to believe that there is a world external to me. I must accept, for practical purposes, the belief that other people in general are honest, that the books I read strike a note of seriousness, that they are honest. I must believe that other people act in general and think in general, in much the same way as I do, that they eat and sleep, that they reproduce, that they work for their livelihood. I must accept in good faith, in short, a universe around me with some order and some integrity, in order merely to continue living myself. Don’t you say the same thing?

Mr. Holmes: Even the scientist finds himself confronted by laws which existed before he investigated them he, too must have faith in these laws. The philosopher must finally reach a conclusion which he accepts through faith. The practical psychologist also starts with the assumption that life already is. We must and do live by faith.

Mr. Sills: Let us take the case of the scientist, whether physicist, chemist, biologist or psychologist he believes that the evidence of his senses can be relied upon.

Mr. Holmes: In that way he has faith in himself, doesn’t he, faith in the integrity of his own being?

Mr. Sills: But what I am getting at is the faith that the experiments imply, an antecedent faith in the man’s own operations. I have faith, for example, that a yardstick always remains a yardstick and always measures the same, that is a yard, that if I measure a tree and find it to be six feet tall and then put the measuring stick against a man and find him to be six feet tall, that they are the same height, that the measuring stick does not change in its transfer from the tree to the man.